At around this time of year, the Legislative Analyst’s Office releases a summary about the budget in preparation for next year’s budget proposal that will come from the governor in early January. Below is an excerpt just for higher ed. A link to the full document follows the excerpt.

==================

UC, CSU, and Hastings

Provides $2.8 Billion in General Fund Support for UC. The budget provides UC with $2.8 billion in General Fund support—an increase of $467 million from 2012–13. Of this increase, $200 million reflects a shift of funds used for paying general obligation bond debt service from a separate budget item to UC’s support item (with no corresponding increase in state costs or total UC support and capital funding). The remainder consists of various augmentations, including a $125 million increase linked with a prior–year budget agreement that the university hold tuition levels flat in 2012–13, a $125 million (5 percent) base augmentation for 2013–14, a $9 million increase for lease–revenue debt service, and a $6 million increase for retiree health benefits. In addition to state support, UC expects to receive roughly $2.5 billion in student tuition payments. (The Cal Grant Program will pay about $760 million of this amount on behalf of students.)

Provides $2.6 Billion in General Fund Support for CSU. For CSU, the budget provides $2.6 billion in General Fund support—an increase of $304 million from 2012–13. This increase consists of various augmentations, including $125 million for holding tuition flat in 2012–13, a $125 million (6 percent) base augmentation for 2013–14, an $18 million increase for lease–revenue debt service, and a $34 million increase in health care costs for retired annuitants. In addition to its General Fund support, CSU expects to receive about $1.9 billion in student tuition payments. (The Cal Grant Program will pay about $430 million of this amount on behalf of students.)

Provides $8.4 Million in General Fund Support for Hastings College of the Law. The budget provides Hastings with $8.4 million in General Fund support—an increase of $511,000 (6.5 percent) from 2012–13. Of this amount, $56,000 is intended to cover increased retiree health care costs. Hastings has discretion in deciding how to use the remaining funding. In addition to state support, Hastings expects to receive $34 million in 2013–14 from student tuition payments.

Provides Base Augmentations. As discussed above, the budget provides base increases of $125 million each for UC and CSU. (The administration derived the dollar increase based on UC’s budget, with the amount representing a 5 percent increase for UC and a 6 percent increase for CSU.) Though the increases are largely unallocated, $15 million of UC’s augmentation is for the new UC Riverside School of Medicine, which will begin serving students in 2013–14. (The Governor proposed to set aside $10 million of each university’s base increase for improving the availability of courses through technology. Though the Governor ultimately vetoed this provision, the universities indicate they will honor the administration’s intent for these funds, as detailed in the box below.)

================================

UC and CSU Technology Initiatives

Both the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) will use a portion of their base funding increase to improve course availability through technology, as described below.

UC to Develop New Innovative Learning Technology Initiative. The goal of the initiative is to help undergraduates enroll in the courses they need to satisfy degree requirements and graduate in a timely manner. The UC plans to spread $10 million across the following components.

- Course Development ($4.6 Million to $5.6 Million). The UC plans to develop 150 online and hybrid courses over the next three years. These courses will be credit–bearing and meet general education or major requirements. The university will select the courses using a competitive process run through the Academic Senate.

- Technological and Instructional Support ($1 Million to $2 Million). The UC plans to make technological support available to faculty developing the hybrid and online courses. The UC also plans to fund teaching assistants to help students taking courses remotely.

- Cross–Campus Registration and Course Catalog Database ($3 Million). The UC plans to develop a new data “hub” to support cross–campus registration. The UC also plans to develop a searchable database of the new courses.

- Evaluation ($0.4 Million). The UC plans to collect data from students and faculty to determine the effectiveness of the new courses.

CSU to Focus on Reducing Bottlenecks and Improving Student Success. The CSU Chancellor’s Office plans to distribute $17.2 million among its campuses to promote five objectives. (In addition to $10 million for technology–specific activities, CSU plans to spend $7.2 million specifically for the student success programs described below.) The amount allocated to each objective will depend on the proposals the Chancellor’s Office receives from campuses. The five objectives are:

- Increasing Enrollment in Successful Online Courses. Beginning fall 2013, CSU will expand enrollment in about two dozen existing, fully online courses. The courses, nominated by campuses and selected by the Chancellor’s Office, are in high–demand subjects and have shown better completion rates and student learning outcomes. Students throughout the system will be able to enroll in these courses and receive credit at their home campuses. The Chancellor’s Office will support the development of processes that streamline registration and transfer of course credits for students.

- Replicating Successful Courses and Teaching Methods. Through a review process, the Chancellor’s Office selected several courses that showed improved student outcomes following changes in teaching methods and technology. The university plans to hold six associated summer institutes that will bring faculty who have successfully redesigned courses together with faculty from other campuses who are interested in adopting new approaches. Participating faculty (and their campus departments) must indicate that they intend to transform an existing course from face–to–face to online, hybrid, or technology–enhanced and offer the revised course in 2013–14.

- Advancing Course Redesign. Campuses will compete for funds to redesign 22 existing courses that are high–demand and have high failure rates systemwide. Redesigned courses will be piloted beginning in spring 2014. Successful approaches will be expanded and disseminated in future faculty institutes.

- Implementing Student Success Programs. The goal of this component is to improve overall student success and graduation rates and reduce disparities in these rates between underrepresented students and other students. Campuses will compete for grants to implement various student success strategies such as developing or expanding summer bridge programs, freshman seminars and learning communities, writing–intensive courses, and undergraduate research opportunities.

- Using Technology to Improve Student Advising. Campuses will compete for funds to implement automated degree audits, e–advising, and other planning tools for students.

================================

Requires Annual Report on Specified Performance Measures. The budget package establishes a new requirement for UC and CSU to report annually, beginning on March 1, 2014, on a number of performance outcomes. Among other metrics, the universities are required to report on graduation rates, spending per degree, and the number of transfer and low–income students enrolled. See Figure 8 for a full list of specified performance measures.

================================

Figure 8

Performance Metrics for UC and CSU

|

Metric

|

Definition

|

|

CCC transfers

|

(1) Number of CCC transfers enrolled.(2) CCC transfers as a percent of undergraduate population.

|

|

Low–income students

|

(1) Number of Pell Grant recipients enrolled.(2) Pell Grant recipients as a percent of total student population.

|

|

Graduation ratesa

|

(1) Four– and six–year graduation rates for freshmen entrants.(2) Two– and three–year graduation rates for CCC transfers. Both of these measures also calculated separately for low–income students.

|

|

Degree completions

|

Number of degrees awarded annually in total and for: (1) Freshman entrants. (2) Transfers. (3) Graduate students. (4) Low–income students.

|

|

First–year students on track to degree

|

Percentage of first–year undergraduates earning enough credits to graduate within four years.

|

|

Spending per degree

|

(1) Total core funding divided by total degrees.(2) Core funding for undergraduate education divided by total undergraduate degrees.

|

|

Units per degree

|

Average course units earned at graduation for: (1) Freshman entrants.(2) Transfers.

|

|

Degree completions in STEM fields

|

Number of STEM degrees awarded annually to:(1) Undergraduate students.(2) Graduate students.(3) Low–income students.

|

|

a Six– and three–year graduation rates apply only for CSU.

STEM = Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.

================================

|

Requires Biennial Reports on Cost of Education. In addition to annual performance reports, the budget requires biennial reports from UC and CSU, beginning in 2014, on the costs of education. The reports are to identify the costs of undergraduate education, graduate academic education, professional education, and research. For all four areas, costs are to be disaggregated by (1) Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines; (2) health sciences; and (3) all other disciplines. The first two reports, in 2014 and 2016, may reflect systemwide costs. Two subsequent reports must include campus–by–campus costs. The reporting requirement sunsets on January 1, 2021, following the fourth report.

Sets No Enrollment Expectations. The budget act typically specifies the number of FTE students the state expects the universities to enroll. For 2013–14, the Legislature adopted budget language stating its intent that the universities serve no fewer students in 2013–14 than in 2012–13. Accordingly, the language included enrollment targets of 211,499 FTE students for UC and 342,000 FTE students for CSU. The Governor, however, vetoed these provisions. In his veto message, the Governor stated that institutional performance, rather than enrollment, should drive university funding.

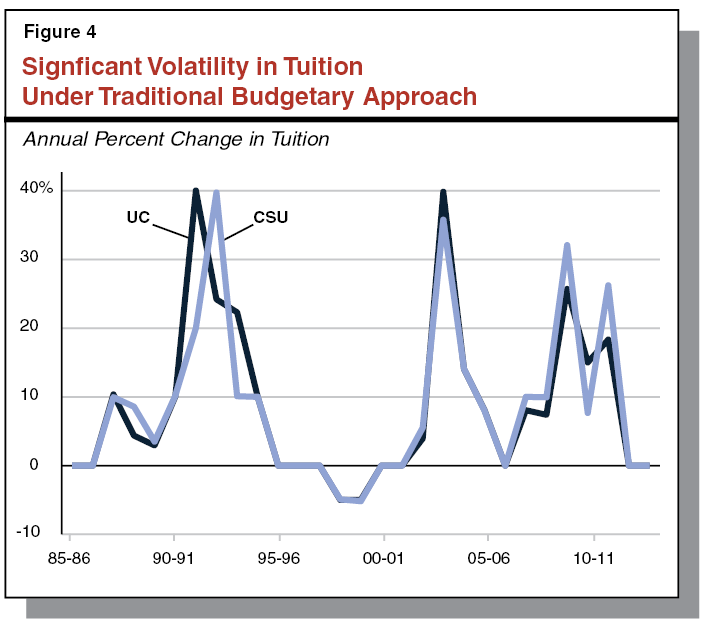

Expects No Tuition Increases. The administration expressed its intent that the universities not raise student tuition levels in 2013–14 and both UC and CSU have indicated they do not plan to increase tuition for resident students. Tuition rates for California resident undergraduates attending UC and CSU in 2013–14 are expected to remain at $12,192 and $5,476, respectively, for the third consecutive year. (The community colleges also plan to hold student fees flat in 2013–14—at $46 per unit.)

Again Eliminates Earmarks. The Governor vetoed virtually all provisions in the 2012–13 Budget Act that designated funding for specific purposes and did not include these spending requirements in his 2013–14 budget proposal. The Legislature restored a number of these provisions—most notably a $25 million earmark for student outreach programs—and stated its expectation that the universities continue supporting other programs—such as UC’s Subject Matter Projects for K–12 teachers—that previously were specified in budget act provisions. The Governor again vetoed the earmarking, citing a desire to give the universities greater flexibility (with the exception of funding for the Riverside Medical School) to manage their resources.

Changes CSU Retirement Funding Model. Traditionally, the state has adjusted CSU’s budget to account for changes in its contributions to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). Under the traditional model, CSU’s CalPERS contributions have been determined by multiplying its current payroll costs by its employer contribution rate. Starting in 2013–14, adjustments to CSU’s budget are to be based permanently on the university’s 2013–14 payroll costs. Because 2013–14 payroll costs are permanently locked in as a base moving forward, CSU will have to fund retirement costs on any payroll above that level from its base budget appropriation. As a result, CSU will have a greater incentive to take into account retirement costs when it makes its initial hiring decisions.

Contains Intent Language Regarding UC Retirement Costs. The budget plan does not designate any funding for UC employer retirement costs, though the university expects these costs to increase by $67 million in 2013–14. Budget trailer bill language states, however, that the absence of such an earmark does not imply legislative support for UC employees paying more toward retirement. In addition, trailer legislation requires UC to apply any reductions in annual debt–service costs achieved as part of a debt restructuring (as discussed further below) towards its pension costs, including its unfunded pension liabilities.

Authorizes New Capital Outlay Process for UC. As noted earlier, the budget plan shifts funds for existing debt service on UC capital outlay projects from a separate budget item to the university’s main support appropriation. It does this as part of a new capital outlay process. Under the new process, UC may pledge its General Fund support appropriation (excluding the amounts necessary to repay existing debt service) to issue its own debt for capital projects involving academic facilities. In addition, the new process allows UC to restructure some of the state’s outstanding debt on UC projects. The new process limits the university to spending at most 15 percent of its pledgeable General Fund on (1) debt service on new bonds for academic facilities, (2) pay–as–you–go academic–facility projects, and (3) existing state lease–revenue debt. In order to use the new authority, the university is required to submit certain information about its capital plans to the Legislature and DOF for review and approval.

Funds a Few Capital Outlay Projects. The budget plan authorizes UC to construct a $45.1 million classroom and academic office building at the Merced campus using the new capital outlay authority discussed above. In addition, the budget provides UC with (1) $5 million from resources bond funds to replace a pier and wharf located at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the San Diego campus and (2) $4.2 million in general obligation bond funding for the equipment phase of a science and engineering building located at the Merced campus. For CSU, the budget authorizes (1) $76.5 million in lease–revenue bond funding to replace academic and classroom space found to be seismically unsafe at the Pomona campus, (2) $5.9 million from general obligation bond funds for the equipment phases of five previously approved capital outlay projects, and (3) $1.8 million from general obligation bond funds to upgrade the structural systems of the Dore Theatre at CSU Bakersfield to correct seismic deficiencies. (The budget also appropriates $1.3 million in general obligation bond funding for the planning phases of a building renovation project at Solano Community College.)

Financial Aid

Provides $1 Billion in General Fund Support for Cal Grants. The spending plan provides a total of $1.7 billion for Cal Grants, including $1 billion in General Fund support, $542 million in federal TANF funds, and $98 million from the Student Loan Operating Fund. This is an $82 million (5 percent) overall spending increase for Cal Grants from 2012–13. Though General Fund spending increases by $331 million from 2012–13 to 2013–14, a large part of this increase offsets a reduction in federal funding. Though virtually all state support for financial aid currently is for the Cal Grant program, the budget package creates a new state–supported financial aid program to be implemented beginning in 2014–15. In addition, the budget makes two changes to California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) operations. The components of the budget package are discussed below.

Creates New Financial Aid Program. The budget package creates the Middle Class Scholarship Program, a new financial aid program for certain UC and CSU students. The program is designed for undergraduate students who do not have at least 40 percent of their tuition covered by Cal Grants and other public financial aid programs. Specifically, students with family incomes up to $100,000 qualify to have 40 percent of their tuition covered (when combined with all other public financial aid). The percent of tuition covered declines for students with family income between $100,000 and $150,000, such that a student with a family income of $150,000 qualifies to have 10 percent of tuition covered. The program is to be phased in over four years, beginning in 2014–15, with awards in 2014–15 set at 35 percent of full award levels, then 50 percent, 75 percent, and 100 percent of full award levels the following three years, respectively. Budget legislation provides $107 million for the program in 2014–15, $152 million in 2015–16, and $228 million in 2016–17, with funding for the program capped at $305 million beginning in 2017–18. If the appropriation is insufficient to provide full awards to all eligible applicants, CSAC is to reduce award amounts proportionately. In addition, the budget package authorizes the Director of Finance to reduce the appropriation by about one–third if the May Revision projects a budget deficit for the next fiscal year. (The budget also provides CSAC with $250,000 for two permanent positions, one limited–term position, and associated implementation costs, as well as $500,000 in ongoing funding for the California Student Opportunity and Access Program to conduct outreach.)

Transfers Support Services to CSAC. For about 15 years, several of CSAC’s administrative support services have been provided by the agency administering the federal guaranteed student loan program in California—initially EdFund, and more recently ECMC (previously the Education Credit Management Corporation). These services include printing, warehouse, mailroom, courier, and information technology (IT) services. The agreement with ECMC is to terminate June 30. The budget provides $610,000 and seven positions to transfer these services back to CSAC, effective July 1.

Creates Reimbursement Mechanism for CSAC to Provide Technical Assistance to Other States. Since enactment of the California Dream Act—Chapter 604, Statutes of 2011 (AB 131, Cedillo)—CSAC has developed an online application that mirrors the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) for students who are unable to use the FAFSA due to their immigration status. Several other states have enacted legislation similar to the California Dream Act and are working to implement expanded aid eligibility. At least one state (Minnesota) has requested technical assistance from CSAC for its initial Dream Act implementation. The budget package creates a mechanism for CSAC to provide assistance to other states and recover the costs of doing so by charging fees for services.

==============================